Chuck, mi hermano

Charles Bowden, my sweet, irascible, intense, tender, brilliant brother died unexpectedly on August 30, 2014, at 5 PM while taking a nap. He had not been feeling well for a few weeks, claiming he had a touch of the flu. His partner and co-author, Molly Molloy, found him in his bed not breathing. Chuck was living in Las Cruces, New Mexico, after spending most of his adult life in Tucson. He wrote books—lots of them—and his words are his legacy.

This is my song to Chuck.

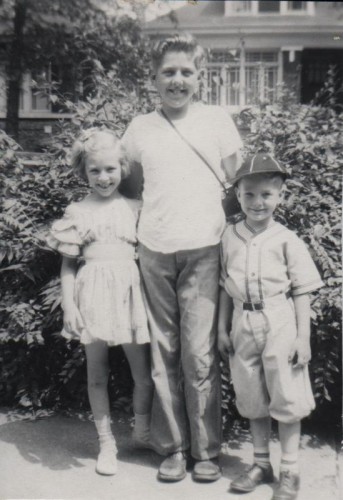

Chuck and a giant tree (photo: Molly Molloy)

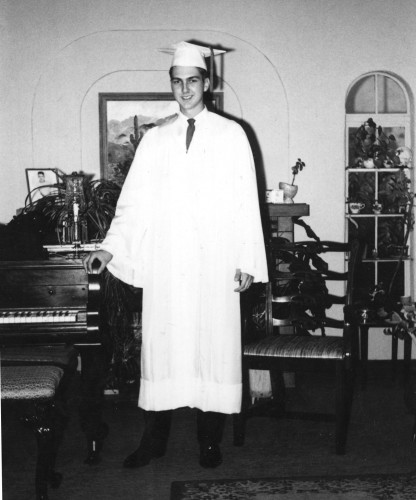

The Bowden family moved to Arizona from Chicago in 1957. My Dad, a retired attorney, told the neighbors that he had discovered buckets of gold in the Arizona mountains: He was a private person and didn’t want his Chicago friends to know his reasons for uprooting the family. My mother told neighbors that the move was due to my childhood asthma. Truth be told, the asthma was improving before the move; the real reason was that Dad had a lifelong interest in the West, and actually pushed to move to Tombstone. Thankfully, my mother insisted on Tucson, and we found a house close to the University of Arizona. After a childhood in Chicago, climbing the mountains by day and seeing the Arizona sky at night was right out of a Zane Grey novel. I remember swimming in a motel pool our first Christmas in Tucson, and mailing photos back to the relatives in Iowa and Minnesota. (We were freezing in the pool but did it anyway.) There were three of us kids–George, Peggy, and Chuckie, the youngest. Now there are only two.

Peggy, George and Chuck, 1949

A lot has been written about Chuck in major newspapers throughout the country these past days. The Chuck our family knew was quick-witted, exasperating at times, a precocious reader, and passionate about what interested him. We were all good kids: We did the chores, respected our parents, and grabbed onto this new life in the Arizona desert. In our house there was never any back talk. Our parents’ word was law. We argued, yes, about politics, religion, and who could drive the car on a certain night.

Chuck and I went to elementary school in Chicago. In Tucson, Chuck attended Mansfeld Junior High, Tucson High, and the University of Arizona. He drove his teachers crazy. Rarely reading the assignments, he delved instead into the literature and history that interested him. Our father, an agnostic, was a scholar of the Bible and Shakespeare, and he tutored us in the elegant words and poetry of both. Dad would sit at the kitchen table with tears in his eyes as he read the soliloquies of Shakespeare to us. We tried our best to understand.

When we were children in Chicago (Chuck was 9, I was 11), we pooled our allowance and enrolled in a classical music mail-order program; we got two vinyl records each month for $10, or $5 apiece. This was a big commitment for us, and we both had to work around the house to earn the money. Chuck and I would lie on the floor by the speakers and turn up the stereo full bore, listening to Rimsky-Korsakov’s Pictures at an Exhibition and the symphonies of Beethoven, trying to comprehend what made them great. Later, Chuck’s love of all musical genres was often a focus of conversation between us. Who was the better poet/songwriter—Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen? (We agreed that Cohen nailed it.)

Chuck loved to cook, and Italian cuisine was a favorite. He taught me to prepare risotto, making sure I never put the cover on the pan. “Always stir the rice, adding the broth little by little. Trust the Italians. They know food.” Dinners with Chuck were always an event—a decent red wine, maybe something off the grill, and talk far into the night. When I was recovering from a serious illness, Chuck drove up to Oregon with his dog, Sam, and cooked for me. My freezer was full of osso bucco and special soups. He was working on an article about photographs, and we had long conversations about how images affect us in deep ways, sometimes forever.

Chuck became involved in the civil rights movement during the 1960s, and was a member of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was on fire about the people he met and sat in Fannie Lou Hamer’s living room in 1967 discussing voter registration and nonviolent protest. Hamer impressed upon Chuck the relationship of racism, sexism, violence and economic injustice, and how all of these factors intersect to keep poor people down. She called him a “white cracker boy,” and he was highly amused by her teasing. Chuck wrote me a letter at that time, pleading with me to join him, as there was a clinic that needed nurses and I was a recent graduate RN from the University of Arizona. I always regretted not jumping in my car and driving to Mississippi.

I believe that Chuck’s life-long interest in those who are trapped behind the walls of racism, poverty, and our fears about who is getting a piece of the pie began in the living room of Fannie Lou Hamer. He told me she was almost totally blind from being beaten by the police while registering people to vote, and yet she saw this country more clearly than any other person he knew.

For the record, Chuck hated NAFTA, the maquiladora program, and the wall that separates us from Mexico. He was unequivocal about this, firmly believing that NAFTA protects the property rights and coffers of corporations, while workers’ rights are ignored. The war on drugs is really the war FOR drugs, and he wrote about these things years before the public listened. I will quote him: “I am tired of people saying they demand a solution. They are lying. What they demand is that nothing change in their lives; that when the sky goes black from smokestacks, someone whip up a witches brew of nuclear magic; that when the rivers go dry, someone suck salt from sea water and ship the pure flow to their house.”

Chuck found solace in birds and spent many months in Patagonia, Arizona watching the swoops and dives of hummingbirds. He told me once, “There is a whole universe out there that is invisible to 99% of the people on earth. It is a layer of reality that people ignore. No one notices the birds.” He went on, “You look at a bird, identify it, and feel like you’re a better person.”

As an adult, Chuck was an avid bicyclist and hiker, at times embarking on death marches across the Arizona desert. He chronicled these experiences in several books, and the family worried about him when he would disappear for weeks. I think he figured that if he was going to write about mass migration of peoples coming north, he needed to feel what this desperation was. He told me he felt guilty when he finished a trek with a steak dinner and a cold beer in some roadside cafe, adding that he had seen people who probably wouldn’t make it out of the desert inferno.

Chuck has a son, Jesse, who is a lot like his Dad–curious about things he doesn’t understand, articulate, and reflective. We are all reeling in the aftermath of this sudden loss to our family. As Jesse told me, “Everyone thinks that Dad is this great iconic literary giant. To me, he was just my Dad.”

My brother’s relationship with our family was strained for many years. He simply quit communicating. The last few years, however, Chuck and I had resumed email contact about his fascination with birds, about my own involvement in border issues, and always about his latest writing project. He and his companion, Molly, planned to speak at the annual Samaritan Border Issues Conference in January, and they were going to stay with my husband and me on our ranch. We were going to have a great dinner, probably risotto, and a special red wine. But mostly we were going to talk and talk far into the night.

He left me far too soon.

Peg,

I am so sorry for the early and unexpected loss of your brother. Our world especially needs heroes like your brother during turbulent times such as we are currently living. The unheard voices of the disinfrancised he spent his life advocating for will need new megaphones. I guess like voices such as your own will need to do double duty…

Please know that I will keep you and your family in my thoughts. The words offering condolences seem so trite and impotent…but they are all we have to offer such pain and grief…

Beverly & Chuck

Dear, dear Peg,

Please accept my sincere sympathy in the loss of your brother. He was remarkable, caring, and willing to do what it takes to make a difference. So are you.

Love,

Faye

Peg,

I still don’t know you in person, so why would I know that Chuck was your brother?

I am so very sorry that you lost him so suddenly, especially as you’d planned a visit from him and Molly. I hope Molly is doing well and has the support she needs, and I hope the same for you.

Your writing about Chuck was vivid and beautiful. Thank you so very much for sharing.

Emilie

Peg,

What a wonderful tribute to your brother. I am so sorry for your loss. Your love for him shines through in your writing. Thanks for sharing. You’re in my thoughts.

Barb Christopher

Dear Peg,

Please accept my sincere condolences for the loss of your beloved brother. He sounds like an extraordinary human being who was fully alive to the world and all of its extraordinary and precious beings. He has obviously left a lasting legacy in his practical passion for social and environmental justice and I’ve no doubt you will continue, in your own way, to continue to fulfill his visions.

Best wishes,

Joseph

Peg ,

I read the article about him in the Green Valley news but did not realize he

was your brother. You are both great human beings.

Offering my condolences for your loss. (I came here as a result of hearing you tonight at Immanuel Pres in Tacoma. So glad to know about you and your work.) Serena Sullivan

Hello Peg, if it is true that nothing really dies, only that energy shifts to stay in this world, your brother is an embodiment of that concept. I really knew nothing about Chuck until I learned of his death. Then I started reading. First, Murder City. Now, Down by the River. Really, I don’t know if I will ever view the world quite the same way. He is still teaching, provoking, pushing, challenging. My condolences to you. Sincerely, Ken

Ken,

Thanks for your kind words and your discovery of my brother’s potent writings. Chuck’s legacy is in the provocative word images he put out there for all of us to see. –Peg

Peg, thank you for sharing your brother with us! Please keep writing! Please consider sharing your thoughts about the Jose Antonio march.

Lisa, Julie’s friend! 🙂